Reflections on The Continuum of The Classics

- Brian Keeler

- Dec 29, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 4, 2021

From the Campagna to Cole’s Catskills - Art in Italy and America

Book Review of “America’s Rome” By William L. Vance

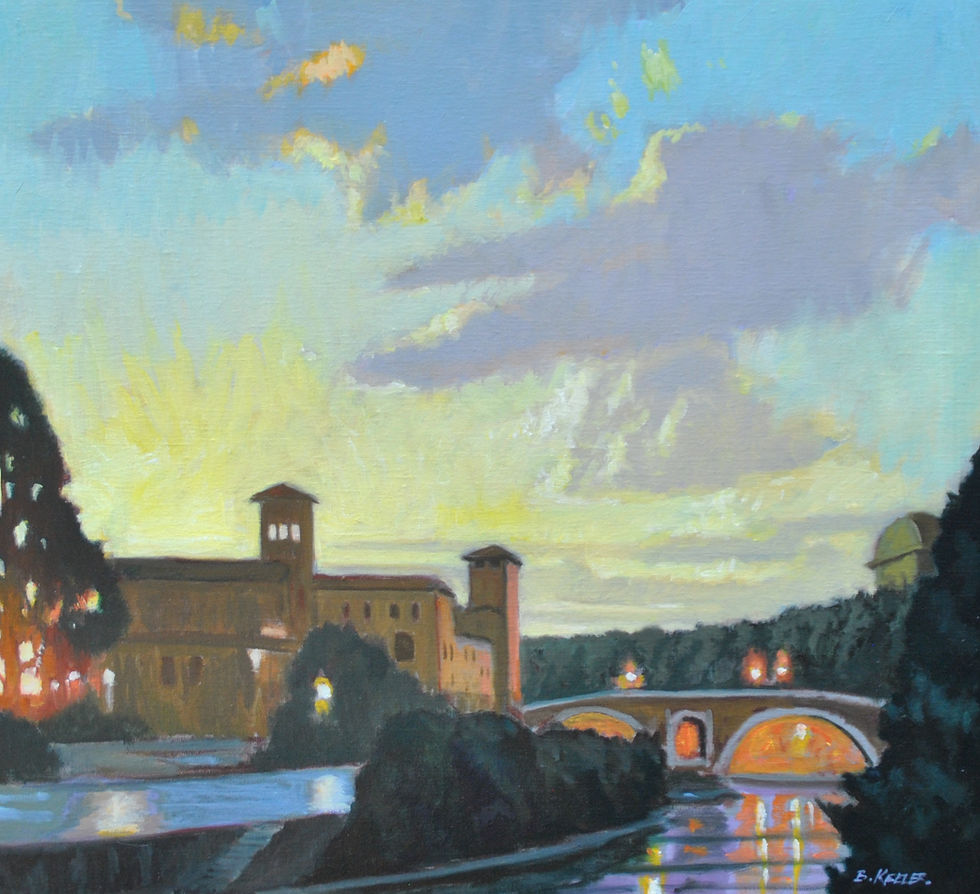

An Essay by Brian Keeler

If ever there was a more thorough book on the importance of Italy and the classics to American arts, it would be hard to find and we would be hard pressed to outdo this volume by William Vance. Although this book was first published in 1989 by Yale University Press, I just came upon it by mere serendipity at the Friends of The Library Book Sale here is Ithaca this fall. Such are the delights of the chance encounter with intellectually stimulating books. This is one of the benefits of living in a university town, where books of this kind are available. It was a steal too, as I got a bundle of other books on the classics and even some DVD’s all for under five bucks!

Well this book is right up my alley. I could also say it is a treasure trove of revelations, insights, new material, while profoundly threading together so many American painters, sculptors, and literary figures. These artists from our nation’s gestational period and early years, while America's creative forces were attempting artistic independence is the author's primary concern. But during this time these artists, and our statesmen too, were seeking connections to our classical heritage and lineage. This is to say they were looking to Italy, its land and light, but also to the rich history of figurative sculpture and literary sources too.

For myself, I have sought similar goals over many years and on many trips to Italy with the same delight and enthusiasm for artistic heritage and discovering anew the beauty of the landscapes and cities that were painted by so many Americans on their pilgrimages to the source, of course along with their European counterparts.

This book has personal relevance also because I have made many canvases with themes inspired by the classics. Why? Well, I like the tradition and learning from examples of the great Renaissance artists. Working from models, or statuary in museums, or from the old masters paintings directly, these sources are intriguing to apply to contemporary settings and view with or modern lens. I have also painted in many of the same areas as the artists in this book have used as a muse.

Where to start? Well how about Margret Fuller for example, as she receives no small part of the explorations of this text. Fuller, who led a remarkable life as an editor of the Dial, an educator, and a women’s rights activist, who engaged with Emerson and the Transcendentalists. She had an affair and children with a charismatic Italian revolutionary and died tragically with him in a shipwreck in New York Harbor in 1850.

A quote from Margaret Fulller from 1848:

“Those who a have not lived, have not seen Rome”

Here is the author’s consideration of Fuller’s Roman undercurrent;

“Fuller is the most interesting conjoiner of American with Roman aspirations, both ancient and modern. She had written in 1845 that Greece and Rome “brought some things to perfection that the world will probably never see again.” And the fact that “our practice” differs should not make us “loose the sense of their greatness." Her essay in the New York Tribune for the New Year’s Day of 1846, foresaw that the “scarce achieved Roman nobleness, a Roman Liberty: The question is a view of the American gaze toward Spanish territories- was whether it would avoid the vulture like propensities of the “fierce Roman bird.” Whether it was to soar up to the sun or stoop for helpless prey.”

We can see from the above that Fuller was fully engaged with politics of her day and that she could draw from the symbolism of ancient Rome to apply these motifs to current events.

This period of American history, and the arts in particular of this era, had been regarded by myself as a sort of dark period, with the paintings that come to mind being those mostly stiff portraits of colonials. How wrong I was. Well, some of those early American attempts at portraiture are still oddly wooden (Gilbert Stuart exempted), but there was indeed more to come.

Two of the painters of the mid and latter part of the 19th century who are brought out splendidly, in this book, in regard to their Roman aspects, are Thomas Cole and George Innes. Cole in particular has become of interest to me for his environmental advocacy as well as his paintings, as he and others like John Muir, and Thoreau were early defenders and portrayers of an American paradise. This beautiful and pristine America that they knew was even then under threat of an industrial onslaught. It is the Roman campagna, the plains and vast countryside to the south of Rome, that becomes their muse while in Italy. We think of Claude Loraine and Poussin and even Turner too, as the European counterparts of earlier generations that plumbed the same light of the area between Rome and Naples. The vast landscape with infinite plains, towering mountains, olive groves, canopy pines, atmospherics and light, along with vestiges of the ancients; the acquaducts and castles, are additions to the appeal of their paintings, as the Italian terra firma is easy to understand for being rich in history and innate aesthetic potential. Thomas Cole also plumbed the rich symbolic history of Rome as well. We can see it in his large and ambitious canvases depicting ancient Rome or mythological groups, such as the series of four painitngs of the "Voyage of Life" in the specially dedicated small room in the NGA in DC. Landscapes and allegories, such as this group at the NGA where meant to be didactic and impart moral lessons as well. In this series, there is reference to the Christian theme of resurrection, as well as the general idea of the impermanence of life.

For us modern day travelers in Italy, the campagna as an area, is somewhat eclipsed by the northern regions of Umbria and Tuscany for topographic appeal. And there is more than a few reasons for this bias and preference. As those northern areas are softer, greener and more diverse offerings with rolling hills of vineyards with the added benefit of being the birthplace of the Renaissance, with the vestiges of the ancient Etruscans.

But before we get carried away with reverie, Wallace levels the playing field with some stark reality and reasons to debunk an overly- romantic view. Here is a passage from an early chapter;

“For both Margaret Fuller and Mark Twain the Roman arena provides a measure for man; for one it is an indication of his apparently limitless potential, for the other it embodies, the universal fraudulence and triviality of his pursuits, his pleasures, and his myths. Historical comparisons, Biblical and classical, had been part of the American consciousness from the beginning, and the relation to the contemporary world to the classical world was for Americans, as representative of the most progressive and democratic nation, more problematic than it was for the French or English, or even Germans.”

In short, Italy and Greco-Roman history have provided a cultural definition for Americans. But the way Twain, and many others like James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence and Nathanial Hawthorne were not enamored with Italy, in many respects, is appreciated by us, as it shows a critical appraisal and not a complete hook-line-and sinker acceptance.

D.H. Lawrence referred to Venice as a dark, dank place of little appeal, Twain was sick of hearing about Michelangelo on his tour through Italy, and Joyce thought of Rome as akin to visiting your great, great grandfather’s decomposing bones.

I personally like the way Wallace has emphasized the connections of the literary and the painterly. Who would have thought that the American writer, Nathanial Hawthorne as steeped in the classics? His novel, the Scarlet Letter is so thoroughly invested in the puritanical mores of America, that it is jolting, if not refreshing to learn of his Roman leanings. His novel, “The Marble Faun” was a quintessential necessity of Americans traveling to the Eternal City for generations. I must go get a copy before my next trip to Italy.

To underscore the dichotomies and embodiment of opposites in the paintings and literature by Americans of the day, Wallace titles a chapter on Hawthorne, “Golden Light and Malarial Shade.” A more striking contrast would be hard to come by, and this phrase embodies the optomism of light with the reality of disease- it cuts to the quick. To suggest part of Hawthorne’s aesthetic, here is Wallace again:

“Hawthorne’s appeal to dream life, his introspection, and his intention (simply stated) to create a world where the imaginary and the actual may meet and modify each other...” “He claims that America lacks the shadows, antiquity, mystery, and “picturesque gloomy” wrongs that make Italy suitable for romance and that his “dear native land” had nothing but “a commonplace prosperity in a broad and simple daylight,’’

We can see that perhaps the tenebrism of Carvaggio’s dark and sometimes violent canvases seen in Rome may have underscored the mysterious shadows that Hawthorne was alluding to. The drama of Caravaggio’s "Calling of Saint Mathew", or even more dramatic, The "Beheading of Holofernes", also by Caravaggio and in Rome, would have appealed as a foil to any puritanical outlook that Hawthorne witnessed in Salem. Then again, that narrative 18th century America certainly has a very dark side as well.

Here is an excerpt from Wallace that sums up the connection between those authors and artists visiting Italy in the 19th century;

“Painters and writers responded by evoking two contradictory visions. One is melancholy and moralistic, the other pastoral and transcendent. On the one hand they present the wasteland of former civilizations, what George Hillard called a “historical palimpsest” in which nature had nearly covered over the ruins of one civilization, the Roman which had conquered and buried another, the Etruscan. As such it is a place of “desolate and tragic beauty,” inseparably connected with the image of Rome,” “ populous with so many visionary forms from regions of history and poetry, vocal with so many voices of wisdom and warning.”

“Palimpsest” is certainly an apt term here. It was an ancient method of writing on velum, which was often scraped off to use again- but leaving traces of the earlier drafts. It was the title of a Gore Vidal novel as well.

We think of too, of the unvarnished truth in this tradition of some of the Neorealist Italian filmmakers of the mid-twentieth century that brought the sometimes heartbreaking cruelty of life to us. Think of films like "The Bicycle Thief", "Umberto D", or "Stromboli" all of which present visions that at once show us unpicturesque starkness, while somehow honoring a tradition as well. Our spirit is enriched and our empathy enabled by these expressions of the travails of the plebeian class in the aftermath of World War II.

It is befitting of this book, that the first image is that of a bronze statue of an American Indian with his son shooting an arrow aimed high above them by Hermon Arkins MacNeil in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City . As Wallace brings out, this is part of the reinventing of the classics and reapplication of the heroic to the new American vision. The "noble savage." is the concept here, as the original Americans became the tabula rassa upon which this ancient lineage of heroes could be applied. The American Arcadia, or ideal is what is being expressed here and it means to give new voice to an ancient narrative.

The aspect of nudity in 19th century America is not given short shrift in the book of Wallace’s and the portrayal of male American Indians would seem to have offered a safe and perfectly natural subject. The author lets us know that American sculptors were taking the Apollo of the ancients and giving the God new form here. The abundance of virtuosic nude sculpture on Rome’s Capitoline Hill or in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence would have offered ample inspirations for those intrepid American sculptors.

To give us the context of the cultural mileu here, especially in regard to the human figure, here is a passage from Wallaces’ book;

“But Away from Rome Brown did succeed in creating various figures of Indians as justification for their nudity did not convince everyone. It merely made Indians as indecent as pagan Greeks. The American Art-Union offered Brown’s first bronze Statuette of an Indaian youth in its distribution of 1849 with the assurance he was a beautiful as Apollo.” "And armed with bow and arrow, like him as he pursued the children of Niobe.”

So we can see that some issues have long life of sensitivity and controversy, namely the depiction of the human figure, clothed, partially draped or nude.

I personally like the aspirational underpinnings, if not altruism that informed the canvases of Inness and Cole and that will be my takeaway from this book. The light portrayed in the canvases of both artists and the spiritual allusions that both expressed have great appeal. Innes with his spiritual structure through a philosophy of pantheism known as Swedenborgianism showed a mission to express something higher through his canvases. The shear beauty of their works inspired by the light of Italy, and then in America too, expresses a higher cause but based on observation.

There was one ancient myth, little known today, and brought out in this book that I find intriguing, which also captivated Inness, Claude, Cole and others. That being, of the deity Egeria, a water nymph, advisor and author of sacred texts. She was believed to inhabit sacred groves. We can see the appeal and relevance in the canvases of these artists as for their predilection for themes of olive groves and lakes. Here is Wallace’s take on this:

“At the same time, she is a sort of fertility goddess, who assured safe childbirth to those who sacrificed to her. Moreover, in the Golden Bough, Frazer suggests that Egeria as a nymph of water and woods is an aspect of Diana, or a local version of her. Innes, in living a summer at Albano and painting Lake Nemi several times , would have know the waters surface “The Mirror of Diana” and would have learned that Apollo’s sister had been worshiped in ancient times in a sacred grove at Nemi.”

I think of Inness's canvases of the beautiful Tiber Valley at Perugia and then taking that same inspiration to paint in America. Also, Thomas Cole's paintings the Roman Campagna and then back here in America painting the Lackawanna River Valley at Scranton or the Oxbow in the Connecticut River at Mount Holyoke, show us how Italy informed their American expressions. In short, there is a continuum and correspondence between Italy and America.

Just as Machiavelli proclaimed to enter into conversations with ancient authors and poets, so did the adherents of Swedenborg’s type of philosophy. Again Wallace on this;

“ the knowledge of correspondences was the chief of knowledge, By means of it the they acquired the intelligence and wisdom of the most ancient people, whoever were celestial men, thought from correspondence itself, as the angels do.”

The book ends with a mention of 20th century painters and sculptors and referred to as a view from the Janiculum, which is the hill above and next to the Vatican where the American Academy in Rome is located. Since more than 200 years have passed since the American painter, Benjamin West first trod the seven hills, the appeal and benefits of the study of Rome still speaks to us, and as Wallace opines; ".. and that beauty that once was must come again."

Thanks Kate- Nice to hear from you. Yes, when we can return to Italy it will be great. In the meantime I'll be offering workshops here in Ithaca outdoors in the spring and summer. Brian

Thanks, Brian. I love seeing your paintings of the greater Wyalusing area. Makes my heart swell.

I'm IN for the next Italy painting trip - when and if it we ever open up! I am so past ready to get over the corna.

Kate